By Julia Schwarz

Artificial intelligence systems often learn through guided trial and error, practicing tasks that become progressively more difficult. But what if training could skip those intermediate steps?

Researchers at Princeton found an unexpected approach: they give AI agents — in this case, simulated robots — a single difficult task and no guided feedback at all. The robots not only completed the tasks but did so more quickly than robots given feedback and instruction.

The approach is so counterintuitive that researchers Ben Eysenbach and Grace Liu were surprised that it worked. "This isn’t the typical method," said Liu, now a doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon, "because it seems like a stupid idea." It doesn’t initially make sense, she said, that instructing the robot to perform a single difficult goal with no feedback would work better than giving it rewards.

This new approach is a departure from current reinforcement learning methods, which use rewards and feedback as part of a trial-and-error technique for training AI systems. By removing all feedback from the training process, the Princeton team left the robots with no alternative except exploration.

"Exploration is a very challenging problem in reinforcement learning," said Eysenbach.

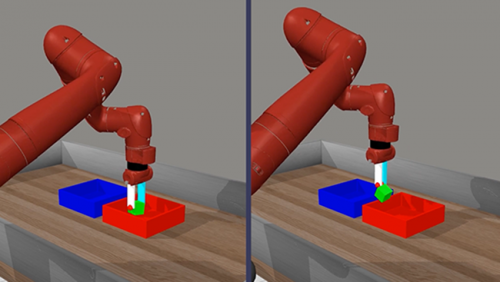

In their experiments, the way the robots behaved, said Liu, was "almost childlike." Told to place a block in a box, the robots would play with the block, testing how it moved. Throughout training, the robots attempted unexpected strategies to reach the goal. "In one video," she said, "we saw it drop the block and then hit it into the box like it was playing a game of table tennis."

"I am not a child psychologist and have no idea what's actually happening in kids' brains," said Eysenbach. "But structurally, some of the things that we're seeing about exploration emerging in the absence of explicit feedback seem a bit similar."

When the machine learns through exploration, Eysenbach noted, the training process is also much simpler for the user. Current approaches to reinforcement learning, he said, are very complicated. Users have to write dozens of lines of code instructing the machine when it’s 20% or 30% of the way toward its goal and give detailed instructions about what to do first and what to do next.

This new approach, he said, would be much simpler. "Users could say: Here's where we want you to go. Figure out how to get there on your own. This could make it possible for scientists and engineers to more easily apply reinforcement learning methods in their work."

The paper, A Single Goal is All You Need: Skills and Exploration Emerge from Contrastive RL without Rewards, Demonstrations, or Subgoals, will be presented at the 2025 International Conference on Learning Representations in Singapore in April. In addition to Eysenbach and Liu, authors include Michael Tang, an undergraduate student at Princeton.