Due midnight Sunday November 21

This is the last lab. Have fun.

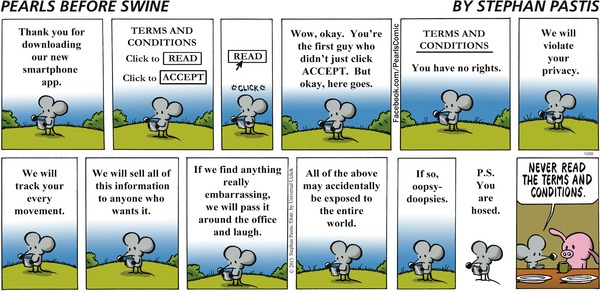

Privacy is much in the news of late, with concerns ranging from identity theft through government surveillance to commercial exploitation of information about our purchases, our interests, our activities, our friends, and everything else. This lab will explore some issues of privacy and access to information.

This is a comparatively open-ended lab, so you may well find ambiguities and fuzzy bits. Don't worry about them, since this is meant to be for exploration rather than precise answers. But please make suggestions to help us improve the lab for next time.

This lab is intended to be more than a Google and Wikipedia exercise; you must cast your net more widely, by using other search engines and other information sources. You will be graded partly on how well you do this, so tell us for each thing what tools you used and how well they worked. Among the alternative search engines you might try are (in alphabetical order): Bing, Dogpile, DuckDuckGo, Yahoo, and Yandex. You can also try Baidu; it's in Chinese but there are sites that let you use it in in English. Anything else is fine too.

Which of these appear to be merely clones of each other, rather than being independent?

There are also sites that do telephone number lookup or that maintain public records; financial sites like Yahoo finance and Google finance provide access to holdings and insider trading; and of course social networks like Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn reveal a lot about their users. Explore; that's part of the exercise. You might find it more productive to spread the lab over a couple of days so you have time to think about possibilities.

As you go along, we want you to collect your observations and comments in a Word or Google Docs document.

Use this template, lab8.docx in Word or Google Docs or the like, so we have some uniformity among the submissions.

Download this file now and begin to edit it. In the following, when we ask you to "report," we're looking for a reasonably organized but not too long description. The questions in the text are meant to start you thinking, but need not be answered literally.

We're not going to grade your writing, but you'll leave a better impression if there aren't too many spelling mistakes, flagrant grammar errors, random formatting, and so on. It's ok to summarize with lists rather than complete sentences, but try to distill the essence of what you've seen rather than just copying and pasting.

You can do this lab anywhere. Some threats primarily affect PCs running Windows, but you should always be cautious, no matter what system you are running. And of course the risks are similar for cellphones, which we're not discussing here. Keep that in mind.

For this section, you should use at least three sources,

not just Google.

How much can you learn about someone just by searching online

information? For yourself or a member of your family or someone else

close to you, see how much you can discover about that person online.

Examples of the kind of information you might look for include

home address,

telephone number, age, birthday, education, employment,

political contributions,

sports and hobbies, organizations and memberships, price of their home,

names of other family members (like mother's maiden name, for example),

activities and interests. Can you find a picture? Was it one that you

knew about?

It might be possible to get information by searching for a phone

number or street address or social security number. (It's a bad

idea to search for your own SSN!) Do phone numbers or addresses

reveal family names? Is information always consistent?

Can you find a good picture of your home (or a friend's) with maps

from Google, Microsoft or Apple? Which one of these gives the best

image? Can you make out your car or some other possession? How much

might the house be worth? See, for example,

Zillow.

If you visit Zillow, what kinds of addresses does it show you without

being asked? How does Zillow compare to

Trulia? Which one appears

to reveal more information, or are they about the same?

What does your Facebook page reveal about you that you find

surprising or worth thinking about?

There's no need to go overboard on this; the goal is definitely not

to invade anyone's privacy, but to get a sense of the accessibility of

ostensibly private information.

As we saw in class, the mere act of visiting a web site reveals

information about you. There are a variety of sites that report back to

you about what information your visit reveals, or about what

vulnerabilities your system appears to have. Visit some of these and

see what they tell you.

Search for some service or store with several search engines and see

how accurately they geo-locate you. Look for

significant differences in apparent accuracy among Google, Bing and

other search engines.

The specific combination of which browser you use, what fonts you

have available, and a dozen other bits of information can identify you

uniquely, or almost so, to a surprising degree. Visit

Panopticlick and

Am I unique?

How unique are you? Try it with two different browsers.

We've talked about how cookies can be used to track what web sites

you visit, especially "third-party" cookies (that is, cookies that come

from someone other than the web site you accessed directly) that

aggregate and correlate information about your visits to apparently

unrelated sites.

First, how many cookies do you currently have? Record the

rough count, and whether this is before or after you removed cookies

after the lecture about them. The easiest way to find cookies is to use

the browser. In Firefox on a Mac, use Preferences and the Privacy &

Security tab.

In Safari,

Preferences / Privacy.

In Chrome, Preferences / Privacy and Security / Cookies and other site data

/ See all cookies and site data.

Now remove all cookies. Set your browser preferences to allow all

cookies, then visit half a dozen major sites (media, sports and

e-ecommerce sites are good for this, as are search engines and even

universities). Check how many cookies a typical visit deposits. Track

the cookies that are tracking you and look for evidence of linkage,

e.g., updated third-party cookies or URLs after visiting independent

sites. You might find it easiest to use a browser setting that asks

about each cookie individually.

For sites that you visit regularly, see whether they deposit

third-party cookies. See whether the cookies contain interesting

information instead of just long strings of apparently random letters

and numbers. Look at the dates when cookies expire. (In the unlikely

event that your regular sites don't have third-part cookies, you

can try foxnews.com, cnn.com, espn.com, priceline.com and so on.)

Experiment to see whether the third-party blocking mechanism

of your browser works the way you expect it to, by first allowing

such cookies, then removing all, setting up blocking, and revisiting

sites.

The site Blacklight

is a vivid demonstration of how much tracking goes on

at any given website. For example, it reports that it found

44 trackers and 78 cookies from 35 different sites at msnbc.com;

foxnews.com was similar, with 29 trackers and 48 cookies from 17 sites,

including some that attempt to evade cookie blockers. Both sites

tell Facebook when you visit them.

Do some exploring with Blacklight (and any other tools that you

like) and see what kinds of tracking you are potentially vulnerable

to. Explore some plausible sites that you do or might visit.

(If you turn on defenses, these horror shows won't affect you

nearly as much.)

Private Browsing or Incognito Mode in browsers is a partial solution

to some tracking problems. An incognito window will delete cookies,

history, and most other data that was created while you were browsing

with that window, but only from your own computer. If you did

anything that could identify you at the various servers you visited,

that is still recorded somewhere. And your ISP knows what sites you

visited as well. Basically all that incognito mode does is to remove

the local record of what you did, so it doesn't make you invisible and

unidentifiable, just that there's not much if any trace of your

activities on your own computer (which explains its informal name, "porn

mode").

In an incognito window, visit some sites that will deposit cookies;

verify that there are cookies. (News, sports and shopping sites are

good.) Delete the window, then open a new inognito window and check to

see whether there are any cookies preserved from the last time.

The Tor browser is one of the best tools for maintaining some

anonymity and privacy on the web. Tor is a version of Firefox that uses

encryption and a network of relay computers to ensure that the sites

that you browse to can not determine your IP address and thus (if you

use it properly) are unable to identify you.

Download and install the Tor browser if you have not already done

so; you can find it

here.

As we discussed in class, there are ways to limit your risks and the

amount of information that you reveal. Virus checkers are

important, but for ordinary browsing there are plenty of others as well.

Many web sites insist that you provide a working email address

before they will let you register or access some service.

10MinuteMail provides a useful

service: it gives you an email address that's valid for 10 minutes

and shows you whatever mail arrives during that time; that lets you

retrieve the registration key or whatever, without giving away a real

address. Two alternatives are

Mailinator and

Yopmail, which lets you invent your own

email address, and retains mail for that address for a week.

Try a couple of these services. Determine how long it takes for mail to

arrive and how long it persists. (I've had the best luck with mailinator.)

Check your own environment. For your regular browser record your

default settings for cookies, filename extensions, JavaScript,

popups, automatic updates, downloading, software, installation, programs

that start automatically, etc. If your mail reader provides a previewer

that interprets HTML and thus is subject to web bugs, try sending

yourself mail with a reference to an image in your public_html

directory, i.e., http://your_netid.mycpanel.princeton.edu,

to see whether the image is retrieved and displayed.

Check what plug-ins and add-ons are already installed in your

browser. Among those you might consider adding are AdBlock Plus, uMatrix

Origin, NoScript, Privacy Badger, and Ghostery; each reduces your exposure to

various kinds of tracking and potentially harmful content. As a bare minimum,

you should run Ghostery and Adblock Plus or uMatrix Origin.

Install

Ghostery,

which works in most browsers. This extension detects and disables

JavaScript trackers, which would otherwise report your page visits and

activities to advertising aggregators. Determine how many trackers

Ghostery reports that it is blocking. Visit some sites to see how many

trackers are in use. Try to find the highest number possible; there

might even be a small and worthless prize for the person who finds the

worst offender.

Reconsider your Facebook privacy settings. Bear in mind that most

Facebook information is readily available outside your own list of

friends and networks; the same goes for other social networks,

including Instagram (owned by Facebook), Snapchat, Twitter, and LinkedIn

(owned by Microsoft).

Finally, if you saw anything interesting or suspicious that we didn't

ask about specifically, or if you have any thoughts on how to improve this

lab, we'd like to hear them. There are a couple of wrapup questions in

lab7.docx that address this:

Thanks.

When you're all done, convert lab8.docx to lab8.pdf

and upload it to the CS tigerfile for Lab 8:

https://tigerfile.cs.princeton.edu/COS109_F2021/Lab8.

Part 1: Personal Information

Part 2: What Else Do They Know About You?

Part 3: Cookie Crumbs

Part 4: Tracking the Trackers

Part 5: Defenses and Countermeasures (1)

Part 6: Defenses and Countermeasures (2)

Submitting your Work