| The same screen at three different resolutions | ||

|

|

|

| 1024 x 768 | 800 x 600 | 640 x 480 |

Due Sunday October 3 at 11:59 PM

My thanks to Xi Chen and Darby Haller for helping to update the instructions for Fall 2019.This lab will show you how to make your own pictures, logos and background images for your web page instead of mixing and matching the ones you've found on the Internet. The lab is meant to be very flexible about specifics, though there are particular tasks that you have to do. There are a number of graphics programs available, and you can use any or all of them to taste, since they all provide the same basic features. This list covers the most common ones:

Use whichever one you like. We won't be at all picky about details of what gets turned in, but do your best to submit what's asked for.

The text refers to Photoshop in regular black text.

Notes for GIMP are in red.

There will undoubtedly be glitches; please let us know about any serious

problems. Thanks.

Important: Material on other web sites may be subject to copyright, and there are both legal and University restrictions on what you can do with copyrighted material, including images and sound. The law is evolving in this area and copyright holders can be very aggressive in asserting their rights (and sometimes more than their rights). You should be aware of the University's policy on intellectual property rights.

In part, this says

"If you want to use a copyrighted work, you should make a good faith effort to determine whether such use constitutes a 'fair use' under copyright law or seek permission of the copyright-holder. As a general matter, you are free to establish links to Web pages. But you are not generally free to copy or redistribute the work of others publicly -- even if you found it on the Internet -- without authorization. Attribution does not resolve the issue of whether the use is permitted under copyright law."

Accordingly, you should be especially careful of images or sounds that might be of commercial value to their copyright owners. If a site has an explicit copyright notice, you should not copy anything from it.

For purposes of this lab, and in creating other web pages, you should add a citation for each image or sound that you link to or copy; this is equivalent to citing sources of quotations in a paper. If there is any ambiguity about whether a sound or image is copyrighted, use a link, not a local copy. Of course if you use your own pictures, copyright is not an issue.

Part 1: How digital images work

Part 2: Creating your own images

Part 3: Using image filters

Part 4: Face pasting

Part 5: Submitting your work

| In this lab, we will highlight instructions for what you have to submit in a yellow box like this one. |

The computer's screen is divided into a large number of tiny dots of color called pixels ("picture elements"). These dots are so small that, to the human eye, they appear to make a continuous picture, but if you zoom in on any computer graphic, you will eventually begin to see the blocks of solid color of which the image is composed. To give you an idea of their size, the dot of an "i" is often represented by a single pixel.

A typical laptop screen displays at least 1024 pixels in the horizontal direction and 768 in the vertical, making almost 800,000 pixels. This figure is known as the resolution. A laptop screen or flat panel display shows a fixed number of pixels, so changing the resolution may show you fewer pixels without changing the image size or it may try to spread the image pixels over the screen pixels, which can cause fuzziness and distortion.

The same screen at three different resolutions 1024 x 768 800 x 600 640 x 480

Each pixel has its own color, typically represented by three values, one for red, one for green, and one for blue (RGB). These values control how much of that color appears in the pixel. Black would be all zero values, while white would have maximum values. Pure red would have the maximum red value, while bluish-green might have green and blue values set to half of the maximum and the red value set to zero. Shades of gray have the same values for their red, green and blue components.

In HTML, rather than use names for colors as described in Lab 1, you can also use the RGB definition of the color. Instead of using a color name in the color attribute of the font tag, use "#rrggbb", where rr represents how much red, gg represents how much green and bb represents how much blue. The values are in hexadecimal, so each hex digit ranges from 0 to F. This means that the range for each 2-digit color is 00 to FF, or in decimal, 0 to 255. For example

<font color="#1e90ff">This is DodgerBlue</font>does the following

This is DodgerBlue

An image may originally be represented as a bitmap, which uses a small fixed number of bytes for each pixel. This preserves the image perfectly but takes much more space than is necessary. Since most images have large blocks of constant color, we can use that information to group pixels and store less information about them. If there are 100 blue pixels in a row, it's more efficient to remember "100 blues" than to remember "blue, blue, blue, ..., blue, blue".

Taking advantage of pixel similarities to reduce the stored information is an example of compression. There are several standard compression techniques in widespread use:

Transparent Not Transparent

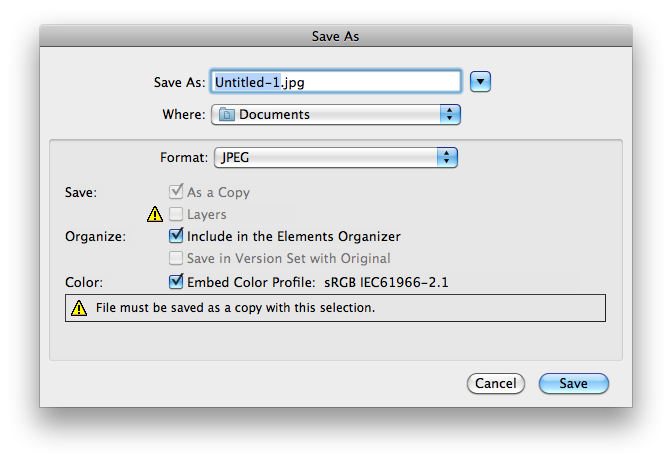

When you save an image as one of these types of files, use "Save As..." and choose GIF, PNG or JPG as the format.

Be sure that you set the file format to JPG, PNG or GIF before you save the file. Do not use the .psd extension that is the default in Photoshop.

GIF works well for images with a restricted number of colors but not for photos. Perhaps surprisingly, JPG is good for photos but not so good for solid blocks of colors, since the compression process can introduce visible artifacts like ripples. For those, PNG is likely to be a good choice.

There are many other image file formats. TIFF, the Tagged Image File Format, is often produced by cameras. TIFF may provide lossless compression, but generally TIFF files are compressed. Cameras also often provide a RAW format that is pretty much unprocessed ("raw") image data.

To create and edit images, you must use an image editor like Photoshop or GIMP. Image editors have lots of menus with lots of sub-menus. They usually display one or more large canvases with a palette of tools. Choosing a paintbrush and dragging it onto the canvas works much like painting in real life. Choosing the paint bucket and clicking on an area will fill it with the current color. There are erasers and air brushes for retouching, features for resizing and reshaping and recoloring, and ways to add text as well. This lab is meant to encourage you to experiment with these options.

Once you have drawn an image, you may wish to play with image filters. These can be found on the Filters menu in Photoshop and GIMP. These image filters (e.g., Sharpen, Emboss, etc.) will examine and possibly change each pixel in the image. The Sharpen filter, for example, looks for edges (places where the color changes dramatically) and enhances those.

Blurry image After Sharpen

Many filters only work on images with 16 million colors (24-bit color). This is usually because they make subtle color changes to the image and need to use many different shades.

Now it's time to experiment with some images. The pictures in this section illustrate Photoshop and GIMP; if you're using another program, read this for the general idea, then find the equivalent mechanisms in your program.

When you start the program, you should see a large window with toolbars and an empty gray area in the center. This center area is where your images will appear when you edit or create them. This image shows Photoshop:

To the left are a dozen or more tools; mouse over them to see what they do. On the right is a color selector. By clicking on the color you wish to use in the palette, you can cause it to be the foreground color. This is the color that will be used when you draw with the paintbrush. By right-clicking, you can adjust the background color, which is the color used for fills and some other changes.

If you are using GIMP (we're using GIMP 2.10 as an example), the display will look like the one below, with a toolbox on the left and an image area in the middle. The two overlapping white rectangles near the middle of the left are for setting foreground and background colors; mouse over them to see.

Start a new picture with File / New (left: PS, right: GIMP):

A large window should appear; this is your canvas. Using the different tools available, you can paint on it with the mouse.

If you are unsure what a particular tool does, hold the mouse over its button. If you make mistakes, just choose "Undo" from the Edit menu to undo your last action.

To shrink or enlarge an image, choose Image / Image Size. (In GIMP, use Image / Scale Image.)

This should change your picture to a new size with the same aspect ratio. If it doesn't then it is likely that your picture got stretched or squeezed in one dimension. Photoshop links the height and width automatically, so this won't normally happen. (GIMP has a lock to preserve aspect ratio.)

Unlike resizing, cropping an image will make it smaller by cutting off the edges. Click on a selection tool (dotted-line box, lasso, or quick select). Click on a part of the image and drag to create a box. Select "Crop" from the Image menu (or use the crop tool). Everything outside that box should have been removed from your picture.

Finally, you can change the picture back to its original size without enlarging the part you have drawn. Choose Image / Canvas size and choose a new size. This should increase your drawing area. The new space is filled with the current background color.

You can do this analogously in GIMP. You can shrink or enlarge the canvas by setting "canvas size" from the image menu. However the canvas size is not exactly the same as the image size. Sometimes you need to use "Layer to Image size" from the Layer menu to fill the new space with current background color.

If you are saving your file as a JPG, check the current compression rate:

Here is the GIMP File / Export as dialog box. Save the file as .jpg or .png, not as .xcf.

You don't need to create a high-quality image in this part, though you should try to do better than this pathetic effort:

To best experience the image filters, you will open and edit a real photo image now.

The image should show up in its own window within the main window. As before, adjust the Zoom Level to your preference. (If the control is not there, click on the magnifying glass to make it appear.) Notice that you can edit and resize this image in exactly the same way as you did with the other image you just created.

Now we're ready to try the built-in image filters, which are on the Filter menu.

| Try at least 3 of the filters and save the results as different files using the "Save As" option. You will be submitting these images at the end of the lab. |

If you're interested in how filters work, try creating your own.

Try to figure out which filters have the following effects:

Ever wonder about photos of Elvis and the president shaking hands? It's called photo-retouching and one of its entertaining applications is face-pasting. Using graphics tools, you can cut someone's head out of one picture and paste it onto to the body of someone else in another picture, or do other merging of picture components. Here's a rough example; I am sure you will not be amused, and I know that you can do a lot better.

| Image1 | Image2 | New and improved |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Editing isn't limited to faces; here is a faked image of someone about to have a very bad day. Fake images have gotten much better as computer power has increased, and today's so-called "deep fakes" can be very difficult to distinguish from real images. What we're doing here is a simplistic version.

| Find an interesting picture somewhere and paste pictures of yourself and/or your friends and/or someone or something noteworthy into the picture. (Anything pasted onto anything, basically.) Blend your picture in with the background as well as you can; we'll be looking for a good job. Save the original images and the final product for submission. |

After you paste in the person from the first image into the second image, GIMP will have this image in a higher layer. This is good because it allows you to move it around, but it will prevent interaction with the background image. Once you have it in the right spot, right click on the pasted-in image, go down to layer, then click anchor layer. This will merge it with the background image.

Be sure to save often. You will probably invest a lot of effort in this, so don't let some random problem destroy your work. At the end of the lab, you will need to submit this image.

Here are a few tips:

Place all of your work online and accessible through a file called lab3.html in your public_html directory on cPanel.

|

|

Please do check all the links. If we can't read it, we can't grade it, and you can't get credit for it. Please use the proper filenames. When everything is working, then

Upload lab3.html and your other files to the CS dropbox for Lab 3: https://tigerfile.cs.princeton.edu/COS109_F2021/Lab3. Thanks.